By Malota Studio — December 2025

In the rugged mountains of South Khorasan province, a discovery that could reshape Iran’s mining landscape has emerged from beneath layers of ancient rock. But separating the headlines from the hard data requires a closer look.

A Discovery That Turned Heads

When Iranian authorities announced in late November that exploration teams had uncovered a substantial new gold vein at the Shadan mine in eastern Iran, the news rippled through international mining circles and financial markets alike. The Ministry of Industry, Mines and Trade validated the find, and within days, reports from AFP to regional outlets were buzzing with impressive figures: more than 61 million metric tonnes of newly identified ore.

For a country operating under international sanctions and seeking ways to bolster its economic resilience, the timing could hardly be more significant. But what do these numbers actually tell us? And more importantly, what don’t they tell us yet?

This isn’t just about tonnage. It’s about what lies within that tonnage—the grade, the extraction complexity, the capital requirements, and ultimately, whether this discovery can translate from geological promise into economic reality.

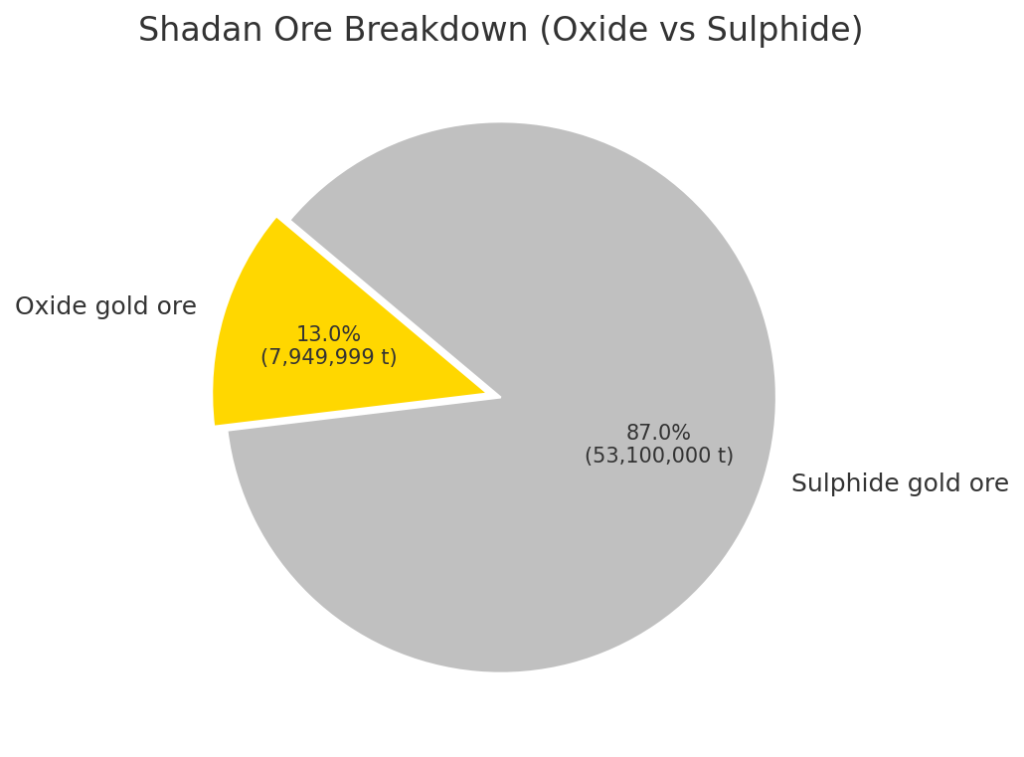

Breaking Down the Numbers: Oxide vs. Sulphide

The headline figures from Shadan are striking. According to multiple reports validated by Iran’s mining ministry and carried by international wire services, the newly identified vein contains approximately 7.95 million tonnes of oxide gold ore and 53.1 million tonnes of sulphide gold ore—roughly 61 million tonnes in total.

But not all ore is created equal, and this is where the story gets more nuanced.

Oxide ore, that smaller 7.95-million-tonne portion, represents the low-hanging fruit. In mining parlance, oxide ores are the kind you want to find first. They’re weathered, oxidized near the surface, and crucially, they’re amenable to relatively straightforward processing methods like heap leaching or conventional cyanidation. This means lower capital expenditure, faster time to first production, and quicker cash flow—critical factors for any mining operation, but especially so in a sanctions-constrained environment.

Sulphide ore, on the other hand, is a different beast entirely. That larger 53.1-million-tonne deposit represents substantial long-term potential, but it comes with a catch. Sulphide ores typically require more sophisticated metallurgical treatment—flotation circuits, pressure oxidation, or roasting—before the gold can be recovered. This translates to higher upfront investment, longer development timelines, and more complex operational requirements.

For Iran, the presence of nearly 8 million tonnes of oxide ore is significant because it suggests the possibility of bringing production online relatively quickly, generating revenue that could help finance the more capital-intensive sulphide processing later. It’s a phased approach that many mining operations worldwide have followed successfully.

Below is the most widely reported quantitative breakdown of the discovery. Multiple local and international reports cite Ministry validation for these figures.

| Measure | Quantity (metric tonnes) | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Oxide gold ore (easier to process) | 7,950,000 | Reported as oxide ore that is generally cheaper to extract. (Times of Israel) |

| Sulphide gold ore (more complex processing) | 53,100,000 | Larger in tonnage but typically needs more complex metallurgy. (Times of Israel) |

| Total reported ore (Shadan new vein) | ~61,050,000 | Sum of oxide + sulphide as reported by local media and AFP-syndicated outlets. (Times of Israel) |

Putting Shadan in Context: How Does It Compare?

To understand the scale of this discovery, it helps to compare it with Iran’s existing gold assets. The country’s best-known and previously largest gold deposit is Zarshouran, located in the northwestern reaches of the country. Recent exploration updates reported in Iranian mining press indicate that Zarshouran’s proven reserves increased substantially in 2024, climbing from 27 million tonnes to approximately 43 million tonnes.

If the Shadan figures hold up under scrutiny—and that’s still an “if” pending more detailed technical disclosure—this would position the new discovery as potentially the largest single-mine ore body in Iran’s inventory. At roughly 61 million tonnes of combined ore, Shadan exceeds even the upgraded Zarshouran estimates.

But here’s the critical caveat that often gets lost in the excitement: ore tonnage is not gold content. A million tonnes of low-grade ore might contain far less recoverable gold than a hundred thousand tonnes of high-grade ore. What matters is the grade—how many grams of gold exist per tonne of rock—and what percentage of that gold can actually be recovered economically.

This is where the Iranian authorities’ announcement, while impressive in scale, leaves some significant questions unanswered. Without published assay results showing average grades, recovery rates, and proper geological classification (measured, indicated, and inferred resources according to international reporting standards), it’s impossible to calculate how many ounces or tonnes of actual gold this discovery represents.

| Mine / Measure | Reported proven ore (metric tonnes) | Reported extractable gold (where given) | Source / Year |

|---|---|---|---|

| Shadan (newly reported vein) | ~61,050,000 (oxide + sulphide) | — | Local media / AFP / Fars (Nov–Dec 2025). (Times of Israel) |

| Zarshouran (largest previously known) | Proven ore reported increase: from 27 million to 43 million mt (exploration update) | Extractable resources cited by Tehran Times reports (2024) | Tehran Times — Dec 2024. (Tehran Times) |

The Strategic Dimension: Why Gold Matters Now

The timing of this announcement isn’t coincidental. Iran has been systematically building its gold reserves over the past several years, a strategy that makes perfect sense for a nation navigating the choppy waters of international sanctions. Central bank statements and government policy documents from 2023 and 2024 have highlighted significant gold purchases aimed at diversifying reserves away from currencies that can be frozen or restricted.

A major domestic gold source changes that equation fundamentally. Instead of purchasing gold on international markets—transactions that can be complicated by sanctions and subject to price volatility—Iran could potentially supply a significant portion of its needs from domestic production. This isn’t just about economics; it’s about strategic autonomy.

The broader implications extend beyond central bank vaults. Gold mining operations create employment—from initial construction through ongoing operations, from direct mining jobs to supply chain support. In South Khorasan, a province that could benefit from economic development, a major mine represents a potential anchor for local prosperity. Previous mining developments in Iran have demonstrated this pattern: new operations create construction jobs during build-out, then transition to steady operational employment, while spurring growth in related services and local businesses.

However, reality rarely moves as quickly as optimism. Environmental permitting, securing financing under sanctions, building processing infrastructure, and addressing metallurgical challenges with sulphide ores—all of these factors will influence the timeline from discovery to first gold pour. Industry experience suggests that even with oxide ores, we’re looking at several years of development work before meaningful production begins.

The Credibility Question: What We Know and What We Don’t

The reporting around Shadan has been extensive. AFP’s coverage, republished by outlets including the Times of Israel, Al Arabiya English, and Kurdistan24, has cited official Ministry validation. Tehran Times and other regional publications have covered the announcement, and the Iranian Mines and Mining Industries Development and Renovation Organization (IMIDRO) has provided supporting context.

This represents a reasonably robust chain of reporting by international standards for preliminary discoveries. Multiple credible outlets independently confirming ministerial statements lends weight to the basic facts: a significant ore body has been identified, the government has validated the find, and the tonnage figures are official.

What we don’t have yet, however, is equally important. The international mining industry operates on detailed technical reports—documents that outline sampling methodology, assay procedures, quality control measures, and resource classification according to recognized standards like the Canadian NI 43-101 or the Australian JORC Code. These reports transform raw geological data into bankable estimates that investors and analysts can rely on.

Without such a report, several critical questions remain open:

What is the average gold grade? Is this 2 grams per tonne? Five? Ten? The difference is massive in terms of economic viability and total gold content.

How is the resource classified? Is this measured (highly confident), indicated (moderately confident), or inferred (preliminary)? The distinction matters enormously for planning and financing.

What are the recovery rates? Even if grade is favorable, what percentage of the gold can actually be extracted using available technology?

What’s the cut-off grade? At what concentration does the ore become uneconomic to process, and how much of the resource falls above or below that threshold?

These aren’t pedantic technical details—they’re the difference between a transformative discovery and a marginal project. Until Iran publishes this level of detail, or engages an independent consultancy to produce it, the Shadan announcement remains a promising beginning rather than a bankable project.

What to Watch For: The Data That Matters

For those tracking this story—whether as analysts, investors, or simply informed observers—certain pieces of information will be crucial as they emerge:

Detailed assay results showing gold grades across the deposit, ideally broken down by ore type and depth. These will allow calculation of contained gold and help predict recovery potential.

A proper resource classification following international standards, distinguishing between measured, indicated, and inferred resources. This provides confidence levels for planning.

Metallurgical test work on both oxide and sulphide ores, showing recovery rates, processing costs, and optimal extraction methods. This determines economic viability.

A preliminary economic assessment or pre-feasibility study, outlining capital requirements, operating costs, production timelines, and financial returns. This answers whether the project makes business sense.

Environmental and social impact assessments, required for permitting and increasingly important for any modern mining operation.

Infrastructure and power availability studies, since large-scale mining requires reliable electricity, water, and transportation networks.

As these details emerge—and if they’re positive—the Shadan story will evolve from an intriguing announcement into a material development in global gold supply. If they don’t emerge, or if the details disappoint, this discovery may join the ranks of geological curiosities that never achieve production.

The Broader Mining Landscape: Iran’s Untapped Potential

Shadan doesn’t exist in isolation. Iran sits atop substantial mineral wealth, much of it underexplored or underdeveloped due to decades of sanctions and limited foreign investment in its mining sector. The country has known deposits of copper, zinc, iron ore, and industrial minerals, in addition to its oil and gas resources.

The challenge has always been development. Modern mining requires enormous capital investment, sophisticated technology, and access to international expertise and markets. Sanctions have made all of these harder to obtain. When international mining companies and banks can’t easily operate in Iran, development slows to a crawl, regardless of the geological potential beneath the ground.

Yet necessity breeds innovation. Iranian mining operations have become adept at working within constraints, sourcing equipment and expertise from countries willing to do business despite sanctions, and developing domestic capabilities where international partnerships aren’t available. The announcement of Shadan suggests that exploration work continues despite obstacles—teams are still drilling, assaying, and mapping deposits.

If sanctions were to ease or change, Iran’s mining sector could see a surge of foreign interest and investment. The geological potential is there; what’s often missing is the capital, technology transfer, and market access that international partnerships provide. Shadan could be an attractive target for foreign mining companies if political circumstances permit—61 million tonnes of ore is enough to warrant serious attention from major players in the gold mining industry.

Economic Ripples: Beyond the Mine Gate

The implications of a successful Shadan development extend well beyond the mine itself. Gold has a unique position in global finance and national reserves, serving as both a commodity and a monetary asset. For Iran, domestic gold production could:

Reduce import dependency, saving foreign exchange that might otherwise go toward purchasing gold on international markets.

Support the national currency, as central bank gold reserves provide backing and confidence in monetary stability.

Generate export revenue, since gold is a globally liquid commodity that can be sold even under sanctions constraints (though with complications).

Attract related industries, from refining to jewelry manufacturing, creating additional value-added activity beyond raw ore extraction.

Demonstrate mining sector potential, potentially encouraging exploration investment in other underexplored parts of the country.

For the provincial economy of South Khorasan, the effects could be transformative if the project moves forward. Remote areas of Iran often face limited economic opportunities; a major mine can become the economic engine for an entire region, supporting not just direct employment but schools, healthcare, housing, and commercial development.

However, these benefits depend entirely on successful development and responsible operation. Mining projects can also bring challenges—environmental impacts, social disruption, inflated local costs during construction, and boom-bust cycles if operations don’t last or if metal prices collapse. International best practice in modern mining emphasizes sustainable development, community engagement, and environmental stewardship alongside economic returns.

The Road Ahead: From Discovery to Development

Mining industry veterans know that the distance from discovery to production is measured in years, not months, and is littered with projects that looked promising on paper but stumbled during development. The statistics are sobering: only a small fraction of exploration discoveries ever reach commercial production.

What does Shadan need to make that journey?

First, the technical work—comprehensive drilling, sampling, and modeling to build a robust resource estimate and understand the deposit’s geometry, grade distribution, and metallurgical characteristics.

Second, the economic analysis—detailed studies showing that the project can generate adequate returns given expected costs, gold prices, and market conditions.

Third, the financing—securing the hundreds of millions (or potentially billions) of dollars needed to build processing plants, mine infrastructure, power supplies, and transportation networks. Under sanctions, this is particularly challenging.

Fourth, the permitting and approvals—navigating environmental regulations, land use requirements, and community consultations to secure the legal right to operate.

Fifth, the construction and commissioning—building the actual mine and processing facilities, a multi-year undertaking requiring coordination of engineering, procurement, and construction.

Finally, sustained operations—maintaining production through commodity price cycles, operational challenges, and evolving regulations over a mine life that could span decades.

Each of these stages presents hurdles. Many projects falter at the financing stage, unable to secure capital. Others fail during permitting due to environmental or social concerns. Some make it to production only to discover that operating costs exceed expectations, rendering the operation uneconomic.

Iran’s sanctions environment adds layers of complexity to every stage. International engineering firms may be reluctant to work on the project. Equipment suppliers may refuse sales or charge premiums. Financial institutions may decline to provide loans. These aren’t insurmountable obstacles—Iran has developed workarounds and alternative relationships—but they slow timelines and increase costs.

A Note of Cautious Optimism

So where does this leave us? The Shadan discovery represents a genuinely significant development for Iran’s mining sector. The reported tonnage figures, if confirmed and accompanied by favorable grades and recoverable gold estimates, would position this as a world-class deposit worthy of international attention.

The presence of substantial oxide ore is particularly encouraging because it suggests a pathway to relatively quick cash flow, which could help finance the longer-term sulphide development. The government’s validation and the breadth of international reporting lend credibility to the basic facts of the discovery.

Yet caution remains warranted. Until we see detailed technical reports, assay data, and economic assessments, the true value of Shadan remains uncertain. Ore tonnage is a starting point, not an end point. The mining industry has seen too many “major discoveries” fizzle when detailed work revealed unfavorable economics or insurmountable technical challenges.

For Iran, Shadan represents potential—potential for increased gold reserves, potential for economic development in a remote province, potential for strategic resource independence, and potential for demonstrating that its mining sector can make significant discoveries despite operating under constraints.

Whether that potential becomes reality depends on the work ahead: the drilling, the testing, the planning, the financing, and ultimately, the execution. The announcement in late 2025 marks the beginning of that journey, not its conclusion.

Conclusion: The Data-Driven Perspective

In an industry where excitement often outpaces evidence, a data-first approach to the Shadan discovery reveals both promise and uncertainty. We have tonnage—roughly 61 million tonnes of reported ore, split between oxide and sulphide types. We have official validation from Iranian mining authorities. We have multiple credible outlets confirming the discovery.

What we await is the deeper technical information that transforms a geological curiosity into an economic proposition. Without average grades, recovery rates, proper resource classification, and economic analysis, the Shadan story remains incomplete.

For those following this development—whether in Tehran, in mining capitals worldwide, or in the financial markets that trade on such news—the message is clear: watch for the data. When Iran publishes detailed technical reports, when independent assays confirm grades and recoverable gold, when economic studies demonstrate viability—that’s when the Shadan discovery will graduate from an intriguing announcement to a material factor in global gold supply and Iran’s economic future.

Until then, we have a promising start, an impressive tonnage figure, and a reminder that beneath the earth’s surface, in unexpected places, significant deposits still await discovery. The question is whether this particular discovery can overcome the technical, economic, and geopolitical hurdles that stand between ore in the ground and gold in the vault.

The world will be watching as those answers emerge.

Sources & References

AFP syndicated reporting via Times of Israel: “Iran announces discovery of major gold deposit” (December 1, 2025)

Al Arabiya English: “Iran announces discovery of major gold deposit” (December 2025)

Tehran Times: “Iran’s largest gold mine reports significant increase in proven reserves” (December 1, 2024)

Kurdistan24: “Iran Unveils Major Gold Discovery” (December 2025)

IMIDRO (Iranian Mines & Mining Industries Development and Renovation Organization) context and background

Malota Studio provides data-driven analysis of mining and resource developments worldwide, prioritizing verified information and technical accuracy over speculation.