The numbers are in, and they’re telling a story we can’t afford to ignore.

In recent years, scientific monitoring agencies and climate researchers worldwide have released an extraordinary wealth of new data on atmospheric greenhouse gases, global carbon budgets, and climate system trends. These findings paint a picture that’s both troubling and clarifying: greenhouse gas concentrations have reached unprecedented levels, natural systems that once buffered our emissions are showing signs of strain, and the window for limiting warming to 1.5°C is rapidly closing.

But here’s what makes this moment different: we now have the clearest picture ever of what’s happening to our planet—and crucially, what we can still do about it. This article reviews the latest data from 2024–2025, breaks down the key metrics in plain language, and shows exactly what they mean for our shared future on Earth.

The Greenhouse Gas Reality Check: CO₂, CH₄, and N₂O at Record Highs

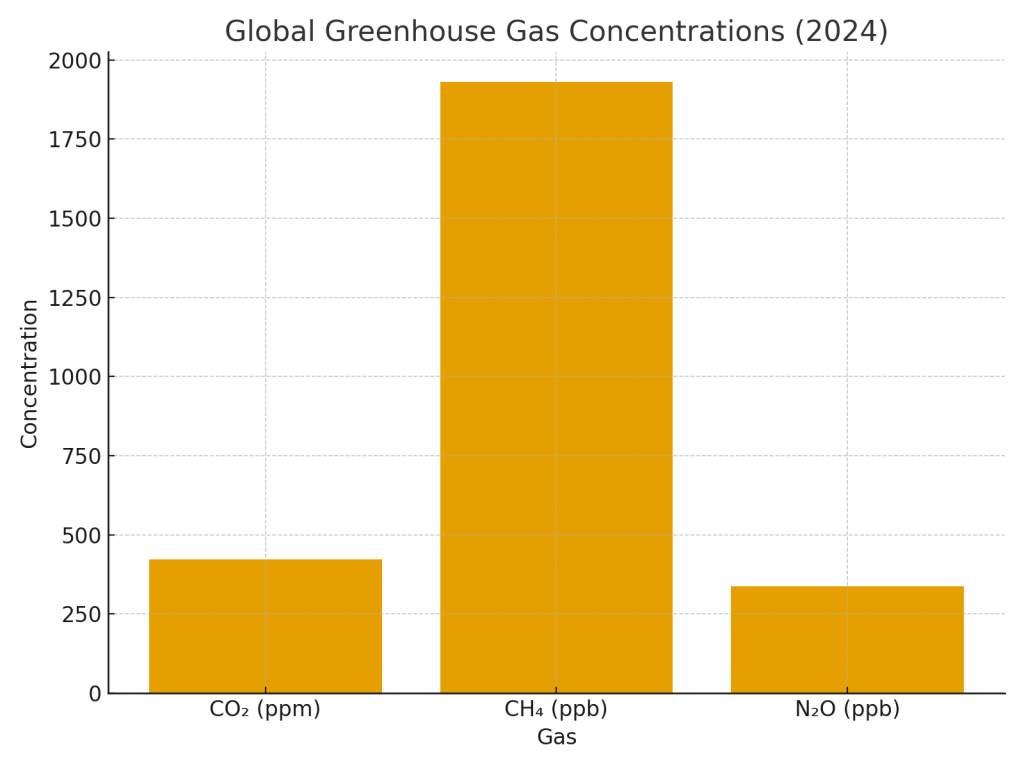

Let’s start with the fundamentals. Recent measurements reveal record-high levels of the major long-lived greenhouse gases blanketing our atmosphere. These aren’t abstract projections—these are direct observations from monitoring stations around the globe.

Here’s where we stand:

| Gas | Global 2024 Concentration (annual mean) | Change since 2019 | Pre-industrial baseline | Approx. % increase vs pre-industrial* |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CO₂ (carbon dioxide) | 422.8 ppm (ESSD) | + 12.7 ppm since 2019 (ESSD) | ~278 ppm | ~52% |

| CH₄ (methane) | 1929.7 ppb (ESSD) | + 63.3 ppb since 2019 (ESSD) | ~720–760 ppb† | ~150–160% (depending on baseline) |

| N₂O (nitrous oxide) | 337.9 ppb (ESSD) | + 5.8 ppb since 2019 (ESSD) | ~270 ppb† | ~25–30% (depending on baseline) |

These are the highest recorded concentrations for these gases in human history—and indeed, based on ice core records, in at least 800,000 years for CO₂.

What’s particularly striking about the 2023–2024 period is the velocity of change. Global mean CO₂ jumped by approximately 3.4–3.5 ppm—one of the largest annual increases ever recorded. This isn’t a gradual drift; it’s an acceleration.

These figures tell us something fundamental: despite decades of climate awareness, humanity continues to inject greenhouse gases into the atmosphere at a rate far exceeding what natural systems can absorb. The consequences of this imbalance are already unfolding around us.

Understanding the Carbon Budget: How Much Room Do We Have Left?

Beyond tracking atmospheric concentrations, climate scientists have developed a powerful framework for understanding our predicament: the carbon budget. Think of it as Earth’s remaining “allowance” for CO₂ emissions before we breach critical warming thresholds.

According to the 2025 edition of the global carbon budget report, here’s where we stand:

- For 1.5°C warming: The remaining carbon budget (from the start of 2025) that gives us a 50% chance of staying below this threshold is approximately 235 Gt CO₂ (or about 65 GtC).

- For higher thresholds: The budgets for 1.7°C or 2.0°C are larger but still finite and surprisingly small given current emission rates.

- The timeline: At our current pace of emissions, we could exhaust the 1.5°C budget in as little as 6 years. Even the 2.0°C budget could run out within a few decades.

This shrinking carbon budget reveals an uncomfortable truth: incremental improvements and gradual transitions won’t be enough. We need transformative change, and we need it now.

The Weakening of Nature’s Safety Net: What’s Happening to Our Carbon Sinks?

Here’s where the story gets more complex—and more urgent. For decades, natural systems have been doing us an enormous favor. Oceans, forests, and soils have been absorbing roughly half of the CO₂ we emit, effectively buying us time. But that safety net is starting to fray.

Ocean uptake of CO₂ showed rapid growth in the 2000s but has been largely stagnant since 2016. Over the 2014–2023 period, the ocean sink averaged around 2.9 GtC per year, absorbing roughly a quarter of our emissions.

Land sinks (forests, soils, grasslands) held at roughly 3.2 GtC per year over the same period—but with significant year-to-year variability that suggests instability.

Most worryingly, newly published research from 2025 indicates a significant decline in the land carbon sink during the 2023/24 period. This appears to be linked to drought conditions associated with a strong El Niño event.

Think about what this means: just when we need nature’s help the most, these natural buffers are weakening. It’s like trying to bail out a boat with a leaky bucket—and the leak is getting bigger.

Real-World Impacts: From Abstract Numbers to Lived Reality

Higher greenhouse gas concentrations, accelerating emissions, and weakening sinks aren’t just scientific curiosities—they translate into changes we can see, measure, and increasingly, feel in our daily lives.

Recent observational reports and studies highlight several deeply concerning trends:

Energy Imbalance: Earth’s effective radiative forcing (the difference between incoming solar energy and outgoing heat) has risen to 2.97 W/m², up from 2.72 W/m² in earlier assessments. This imbalance means the planet is accumulating heat.

Temperature Records: Global surface temperature and ocean heat content are both at record highs. We’re not just breaking records occasionally—we’re shattering them with alarming regularity.

Rising Seas: Global mean sea level has risen by 228.0 mm since 1901 (by 2024 estimates), currently rising at an average rate of about 1.85 mm per year—and the pace is accelerating.

Extreme Weather: Warmer oceans and higher atmospheric temperatures are driving increasing frequency and intensity of extreme weather events: droughts that parch continents, wildfires that consume entire regions, heatwaves that shatter records, and rainfall patterns that oscillate between flood and drought.

The climate system appears to be crossing thresholds that were once relegated to “worst-case scenarios” in scientific models. Those scenarios are becoming our reality.

The 1.5°C Goal: Can We Still Achieve It?

This is perhaps the most pressing question in climate science today. With greenhouse gas concentrations climbing and carbon budgets shrinking, many scientists now believe that limiting global warming to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels is becoming increasingly difficult—though not yet impossible—without immediate, drastic action.

The math is stark:

- Record-high CO₂ levels, accelerated emissions, and weakened natural sinks mean current trends are “off-track” relative to the scenarios the IPCC outlined for achieving 1.5°C.

- The remaining carbon budget for 1.5°C is small; under business-as-usual trajectories, it could be exhausted within a handful of years.

- Even warming of 2°C or higher now appears increasingly likely by mid-century unless major systemic emission reductions occur quickly.

But here’s what’s crucial to understand: these aren’t predetermined outcomes. They’re projections based on current trajectories—trajectories we still have the power to change.

If we do cross these thresholds, the risks extend far beyond environmental concerns. We’re talking about cascading impacts: rising sea levels that displace coastal communities, extreme weather that disrupts agriculture, ecosystem collapse that threatens biodiversity, challenges to food and water security, and large-scale human migration. These aren’t abstract future problems—they’re challenges that will reshape societies.

Why 2023–2024 Was a Pivotal Period: El Niño and Feedback Loops

The dramatic jump in CO₂ and other climate metrics during 2023–2024 deserves special attention. This period appears to represent a convergence of natural climate variability and human pressures—a preview of the kinds of compounding effects we can expect as the planet warms.

A strong El Niño event created conditions that amplified emissions and weakened carbon sinks:

Reduced Plant Growth: Hot, dry conditions across many regions reduced plant growth and photosynthesis, weakening the land’s ability to absorb CO₂.

Increased Wildfires: Droughts and heatwaves created perfect conditions for massive wildfires, which release stored carbon back into the atmosphere—turning forests from carbon sinks into carbon sources.

Ocean Changes: Ocean warming and acidification may be reducing the efficiency of oceanic CO₂ uptake, or shifting it in ways that are less predictable and potentially less stable.

This creates a dangerous dynamic: natural buffers are being eroded precisely when pressures are increasing, creating feedback loops that accelerate the climate crisis. It’s a preview of what climate scientists have long warned about—tipping points where changes become self-reinforcing.

The Path Forward: Science-Based Imperatives for Action

The latest data, research, and trends point to several critical actions if we want to avert the worst climate outcomes. These aren’t suggestions—they’re imperatives backed by the best available science:

1. Deep and Rapid Emissions Cuts Given the shrinking carbon budget, incremental changes are no longer sufficient. We need transformative reductions in emissions from fossil fuels, land-use change, and deforestation. The transitions that once seemed radical now appear necessary.

2. Protect, Restore, and Support Natural Carbon Sinks We need massive investment in reforestation, soil health, protection of existing forests, wetlands, and peatlands. Reducing land degradation isn’t optional—it’s essential. Nature has been our ally; we need to support it.

3. Accelerate the Transition to Renewable Energy Decoupling human development from greenhouse gas emissions is perhaps the greatest engineering and economic challenge of our time—and also one of the greatest opportunities. Solar, wind, and other renewable technologies are now cost-competitive; we need to deploy them at scale and speed.

4. Improve Climate Monitoring and Understanding We need more satellites, better ground-based observations, and continued research into how ecosystems respond to rapid warming. Understanding these systems better helps us respond more effectively.

5. Promote Global Cooperation and Climate Justice Climate change is inherently global. Mitigation and adaptation require coordinated action across nations, with particular support for regions most vulnerable to climate impacts—often those that contributed least to the problem.

Without aggressive action on all these fronts, the scientific community warns that even “2°C scenarios” may become dangerously optimistic.

Conclusion: We Stand at a Critical Juncture

The data from 2024–2025 couldn’t be clearer: we are living through a critical turning point in Earth’s climate history. The evidence is overwhelming, the trends are concerning, and the time for action is now.

Atmospheric concentrations of the major greenhouse gases—CO₂, methane, nitrous oxide—are at their highest levels in hundreds of thousands of years. The natural systems that once absorbed much of our emissions are showing signs of strain. The remaining carbon budget for avoiding dangerous warming is rapidly shrinking. And the climate system itself is shifting in ways that bring rising temperatures, ocean warming, sea-level rise, and increasingly extreme weather.

For those committed to climate action, these findings are indeed a stark call to urgency. The window to keep warming within relatively safe boundaries is narrowing with each passing year.

But here’s the crucial point: the science also offers a path forward.

Through deep emissions reductions, restoration of natural sinks, aggressive deployment of renewable energy, improved monitoring and understanding, and genuine global cooperation, we can still influence the trajectory of climate change. We can still determine how this story unfolds.

The coming decade may well decide whether humanity succeeds in avoiding the worst impacts of climate change—or locks in a future where extreme climate disruption becomes the norm. The data has given us clarity about the challenge. Now the question is whether we’ll respond with the urgency and scale that this moment demands.

The choice, ultimately, is ours to make. But we need to make it now, while we still have choices to make.